#26 TATWTD - GRIEF, part 3

I did a short lecture series some years ago on using the brain for thinking. Likely, that was what I was doing independently in High School American History class when Mr. Cognac called my attention from the window back to New York’s Triangle Fire, and asked, “Would you like to rejoin us, Miss Roberts?”

Bear with me, I’m moving toward a point. But first, I just used the word “moving.” Did you know that when you decide to move (I’m reaching for my coffee mug now at 4:15a.m.), the brain’s frontal lobe emits an electrical signal ahead of one’s thought, that is, it prepares for the thought (to move) before it’s thought. That’s right. I will think to make a move for my mug 3/10th of a second AFTER my brain has acted on my coming thought. I mean, what IS this thing, this three pound, seven-inch long mushy mess of mind mystery that floats under a rigid skull at the top of our necks?

Our Skoshi trustingly yielded to his dying process. David and I suffered the gift of knowing Skoshi was dying. Humans suffer the ability to connect present experience (Skoshi dying) to the remembered past (our history with him) and an imaginable, presently terrible, future (his absence). Grief begins before occurrence.

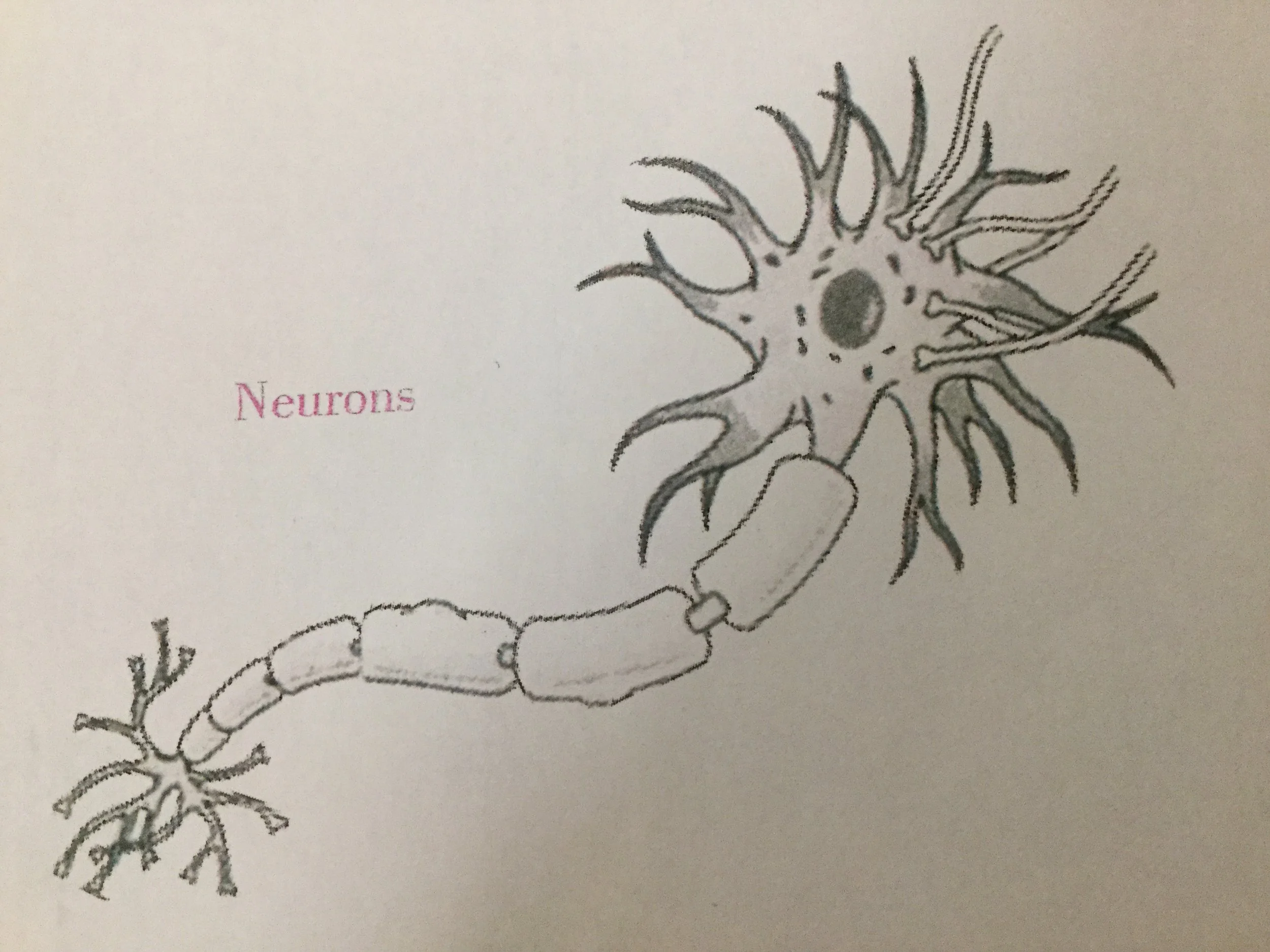

The brain and grief is my subject because in this blog, I’m defaulting to the rational me. It helps me not hurt so much; it’s a strong part of my grief defense. It helps me understand why I hurt so much. I’m convinced that like all thought, behavior, experience, and memory, grief gets born in the trillions of neurotransmitting charges (Synapses).

Everything we think, every memory we store, every new thought we have, all travel between hundred of billions of neurons (about the same number as stars in the Milky Way, by the way) via trillions of synaptic firings sending and receiving information (unless we’re watching television).

I’ve had so many “Skoshi” thoughts, experiences, and feelings since I met him fifteen years ago that my brain has created ever-expanding sturdy synaptic pathways or file cabinets, where all this Skoshi stuff is stored. But. . . . and here comes grief. It’s just that IF a pathway is not used repeatedly, or often, it is abandoned. The abandoning carries pain.

My toe reaches toward the foot of our bed in the night to touch Skoshi’s sleeping place. It is not there. There will be fewer and fewer nights of this reaching before the habit is lost. Who can’t describe the many painful ways our habits of love are diminished, altered, stolen, even forgotten, by the passing of time; by the reshaping of our brains; by our resistance.

It takes time for the brain to settle unused synaptic pathways; to sort between experience and memory. It takes time for old pathways to yield. We want to use the one that says “touch him,” but we may not, and the result is grief. It takes time before grief—described so rationally as “keen mental suffering or distress over affliction or loss” is forced (by the need to live presently) to yield some, to accept remembrance rather than to demand back what was lost. It simply takes time. And it takes the resisted but worthy work of the brain.