#49 A Woman's Briefs -- OBSTRUCTIONS

Give it a try. Pay attention to where your tongue is, where your lips are, when you sound individual vowels and consonants.

“Vowels and consonants?” you say, lifting your voice on the last syllable. Clearly, you are questioning.

Fair enough. Perhaps you’ve forgotten that in the first grade you met letters of the alphabet as vowels and consonants. None of us is old enough to remember, but the Old English alphabet recorded in 1011 by the monk, Byrhtferǒ, held twenty-nine letters. These, of his letters, have since been eliminated: & ⁊ Ƿ Þ Ð Æ.

In the sixteenth century, letters J, U, and the W as we see it were added. Then, oh yeah, in 1835, the ampersand that followed Z was dropped. Long story short? By the time any of us reached first grade, the English alphabet consisted of twenty-six letters. Five of those letters, sometimes six, are called vowels, the others, consonants. Don’t ask me why.

A human’s journey to spoken words begins shortly after birth with cooing vowel sounds. By six months, some multi-syllable babbling places a vowel sound behind a consonant (da, bababa), and finally, nearing a first birthday, babies use a variety of vowels. Not only ‘da,’ but ‘do,’ or ‘di.’ Some sounds remain difficult for children up to age four: sh, ch, j, th, l, r.

My point? Even before a classroom, a six-year-old’s mouth knew to distinguish vowels (a,e,i,o,u, and sometimes y) from letters called consonants. In practice, children had differences down.

Uncle Ed

I have an uncle, Ed, born two weeks after my own birth. That’s a story in itself. Ed and I were four years old when his father’s (my grandfather) brother, Tun, visited from Texas. Tun’s drawl was wide as a chimpanzee’s grin. He entertained our Phoenix families with a string of stories. Once, he mentioned a bear. My little uncle cracked up.

“Oh, Ha ha ha!” Ed burst with the joy of discovery. He blurted, “Uncle Tun calls beh-os, beh-ahs!”

I promise not to belabor this. What my four-year-old uncle did is what young children do without hearing it—vowelization. Ed (and actually, Uncle Tun) substituted a vowel sound for the letter R. “L” and “R” are phonetic “liquids.” (Not that our language is complicated) Unlike other consonants, these two letters let air in the mouth move continuously. Go ahead, say ‘R.’ You’ll see.

Young children have trouble with these liquids. Better to let air flow out on ‘O’ or ‘A’ or ‘E’ or ‘U.’ All other consonants require an Obstacle, Occlusion, Obstruction to air flowing from the mouth. Consonants stop air.

Go ahead. Do it. Notice. Your lips obstruct air when you say ‘P.’ The ‘T’? Without your asking, that tongue you rarely think to thank, pops to the ridge behind your front teeth, obstructing the flow of air but granting a tick sound. Whoa! Notice. The back of your tongue teams up with your soft palate to give you ‘K.’ ‘M’ begins thinking it might slip out on a stream of air but then the lips slam shut to finish it off. Dang!

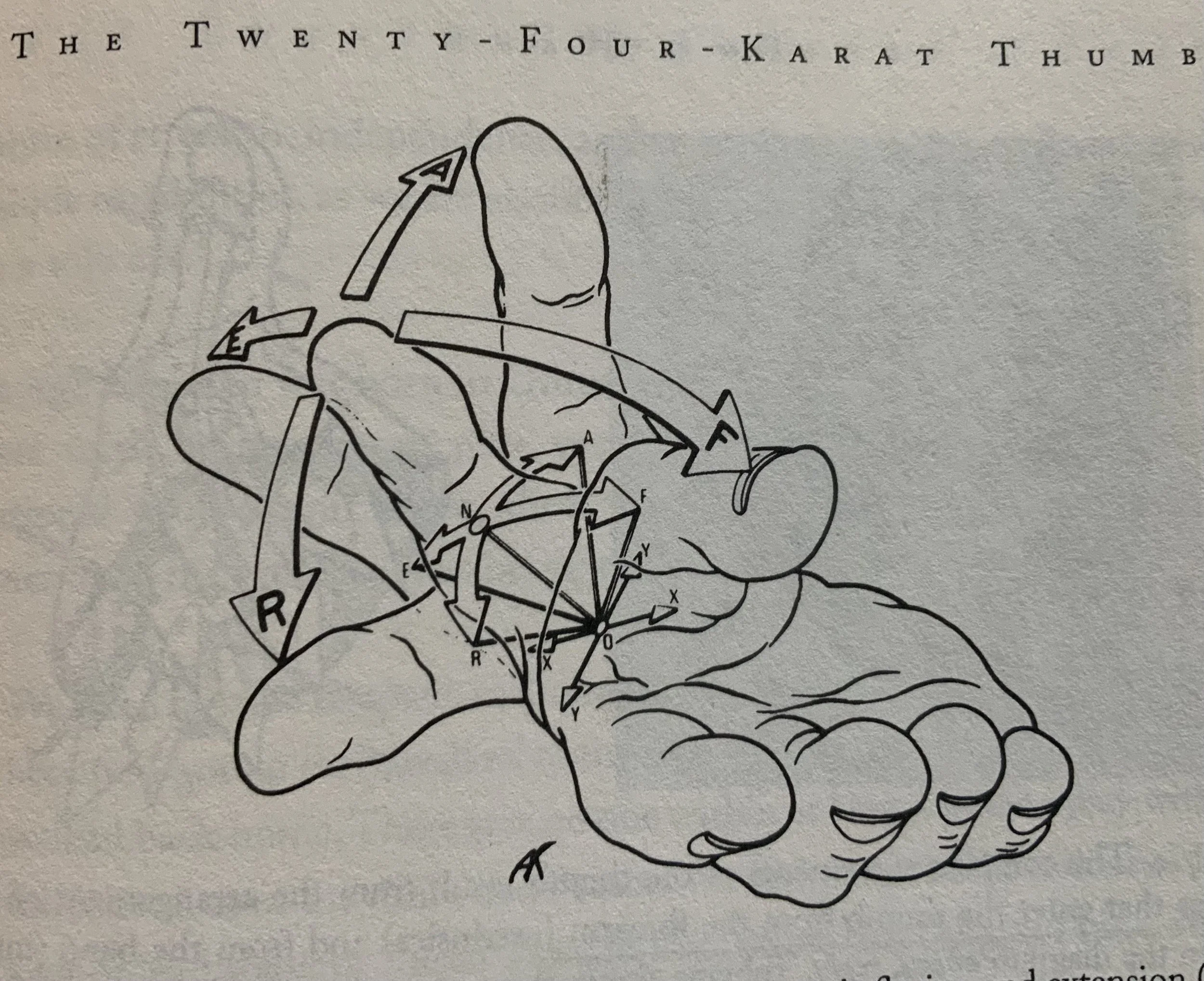

It's just a thought, but while we humans tend to resent or resist obstructions, like the one you see below where a quick path from houses on the hill to a retention pond path has been, ah, obstructed. Deliberately. People are not happy.

Not only might people hurt themselves (imagine the lawsuits!), but when a hard rain finds the eroded path where feet have trod, it forms a rivulet fit for transporting pounds of hillside soil to the ponds below.

Some life obstructions, not only those created by lips, tongues, and teeth, prove beneficial. We may not like them. We struggle against them. We resist restrictions, we who love shortcuts. Sometimes, as in the case of consonants, obstruction bring clarity.

SURE, try to keep people off this path. Obstructions abound.

SCROLL DOWN TO LEAVE COMMENTS