#45 A WOMAN'S (+SCOOTER) BRIEFS

Warning: this is a very long blog posting. Sorry.

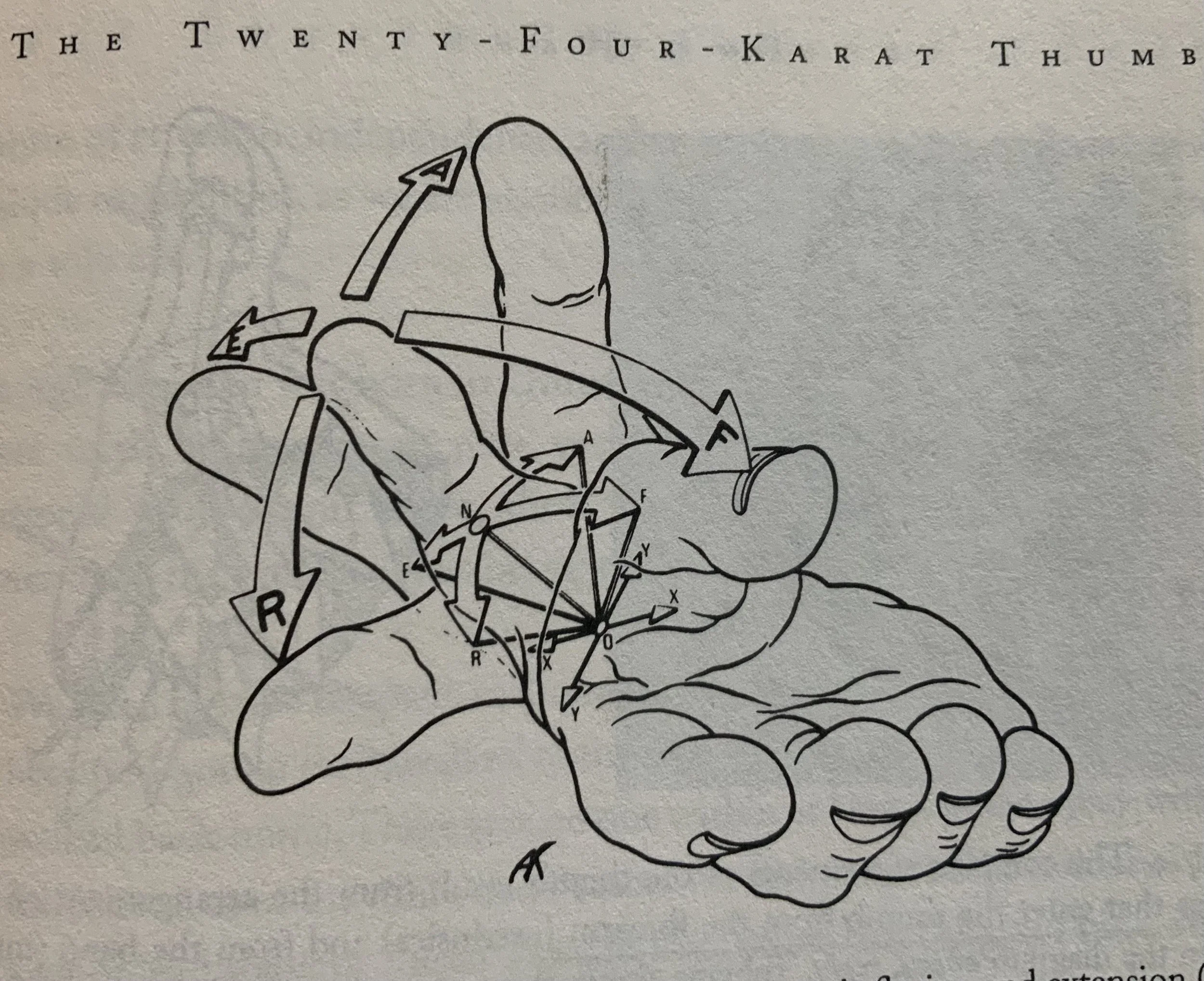

POWER: Pow! Punch! Wham! Boom! This is our usual sense of power.

People love it, fear it, avoid it, possess it, resent it, envy it, misunderstand it, use it, abuse it, pretend it, quest for it, conceal it, flaunt it, brag about it, try to buy it.

The Romans gave English the Latin word for power: potere, a word meaning “The Ability to Affect, To Be Able, or To Exert Influence. There’s no real punch here. Of course, those Romans knew how to have it, exploit it, revel in it, abuse it, wear it, weld it mercilessly, and even make beautiful things by means of it. They did everything but share it.

What the heck is it?

I know next to nothing about the great French novelist, Stendhal. Well, I know “Stendhal” is a pen name for Marie-Henri Beyle. I know he was born in January 1783, and that when he was seven his beloved mother died in childbirth. I know he fled his Grenoble home for Paris when he was sixteen to escape his father’s harsh power. I’ll come back to Stendhal.

Many of you know that I managed to wander in the field of theology long enough to glean a Master of Arts degree; long enough to concentrate on history and grow suspicious of how we of Christendom (like most good people of the earth) do love denying that we love power. In truth, we have grown quite fond of it. We adore the sound of the Greek word for it found in our scriptures: δύναμις" (dýnamis). Power is dynamite!

You’ll forgive me, I hope, for a little review. Christian historian Luke said that Jesus said his followers would “receive power” from God. Luke used dýnamis. That sounds like Boom! Pow! Power! Pow! Pow! But, come on, ancient Greek philosophers, those closer to Luke than we are, described dýnamis as ‘an inherent potential or capacity to affect change, the ability to exert influence.’ (Yawn)

Plukc`gkmkg[s!dig=fg

“SCOOTER! Get your foot off my keyboard!”

“Mom. Where are you going with this? I see a stack of notes beside the computer. It’s too much.”

I push his foot away.

“It’s a Woman’s Briefs entry for the blog.” I say.

“About power?”

“Well, yeah. It’s about what happens to people when, well, when power goes to our heads.”

“Like?” He waits.

“Like, say a person likes power more than goodness. The brain changes. And those aren’t good changes.

“Who said that!” Scooter put on his challenge hat.

“Dr. John Medina, for one. He’s a molecular biologist specializing in brain function. He can isolate and characterize genes involved in brain activity. You know, he’s written all those “Brain Rules” books. Now, how about you let me get back to my work.”

“Has he written Brain Rules for Dogs?” asks Scooter, stretching to threaten my keyboard. “I’m pretty powerful.”

“Scooter, I’m talking about people addicted to power, and what changes in their behavior. Here, read this—”

“Mom!”

“I’ll read it to you. Medina says power will change the brain for good or ill. It’s a bit like fire. You can use fire to cook dinner or burn down your house. Power can benefit or destroy. If power serves a utilitarian ethic . . .”

“Stop! A what?” says Scooter.

“Sorry. Utililitarian ethic. Say a person can choose between a right thing to do, and something that will grant a personal advantage. When that person chooses personal advantage, a utilitarian use, then power—the ability to affect, to control, to enable, to influence—shifts to the dark side of using power. The brain starts rewiring. Well, the brain is always rewiring, but now it builds paths to self-serving behaviors.

“Four things for sure grow in the brain of a power abuser. One: the loss of empathy. You know, an attitude of ‘who cares what happens to them when I get what I want.’”

“I’m pretty powerful,” says Scooter. “Sometimes I pay you no attention when I want to lunge at the geese.”

“Not caring what happens to me at the other end of the leash?” I ask. “But we’re working on that.”

“You’ve got too many notes, Mom. Can you cut to the chase?”

“Not quite yet, sorry. Scooter, people who use power for selfish reasons, yeah, do fail to be empathetic but, and this is important, secondly, they lose the ability to read emotion clearly shown on the faces of others. They can no longer read the intentions of another.

“Oh,” says he in a hurry. I read your face alright.”

“Psychopaths suffer the same incapability. That’s quite a trait to share, right?

“Keep going. What’s the third marker of misused power?”

Medina says that on the dark side of power, feelings of entitlement elevate. Accolades are deserved, not earned. Darkside power believes itself entitled to takes what it wants.

“No dark side for me,” says Scooter. “I really read faces.”

I press on. “Thirdly, people using the dark side of power feel liberated from rules. They make rules for others but feel totally free of keeping any.”

“I’m licensed now,” says Scooter. We finally kept that city rule.”

“Scooter! Stop! Here’s the last evidence of power abusers. This applies to both men and women who use power for personal gain. It might apply to male dogs.

Testosterone levels rise in power abusers. Along with that comes an increase in self-perceived mating values.”

“Mom!”

“But it’s true, Scooter. People dispensing self-serving power find themselves quite sexually desirable. And, since they fail to read emotion in the faces of others, what’s to discourage their opinion?”

“I read faces, Mom.”

“This blog is pretty much not about you, Scooter.”

“Oh.”

“Pull your foot back.”

Now, about Stendhal.

In 1822, Stendhal wrote ‘On Love,’ and in that book he said, “power is the greatest of all pleasures.” Goodness, when power is used to prosper one’s self, it can feel glorious.

Then, addressing Ministers of Government, he wrote, “It seems to me that only love can beat it, and love is a happy illness that can’t be picked up as easily as a Ministry.”

Stendhal is right. Power is pleasure. Let’s not deny it. As a noun, as a thing defined, power is merely the ability to affect or influence. However, once power becomes a verb, whether used by Greeks, Romans, or Americans of Significance, power becomes a tool.

Love can beat it (an antidote?). Even Jesus said that. But boy, not easily.